The ketogenic lifestyle, characterised by its low carbohydrate, high dietary fat consumption, has received a lot of attention over the past few decades for its healing and fat loss abilities. Among some of the most intriguing areas around this lifestyle is its impact on cognitive health, specifically the reduction in neurological atrophy amongst individuals with medically classified Dementia. This condition, marked by the cellular recession within both hemispheres, has become a key talking point within Western populations.

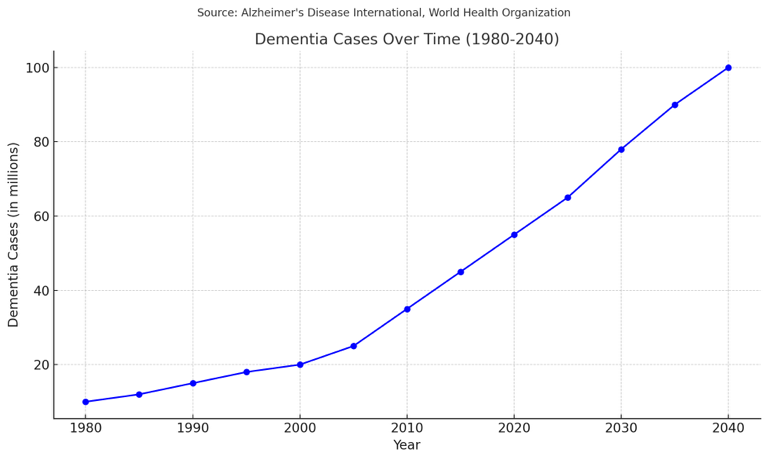

A specific challenge has grown within our society due to the influx of Dementia diagnoses over the past four decades. Currently, we have seen a 450% increase in identification since the 1980s, with it expected to double from recent to figures to those of 2040.

This leads us into a specific question. What has caused this Dementia diagnosis epidemic? Is it the fact that we have better tools to diagnose individuals? Is it because our population is just getting older? Or are there other variables that need to be studied?

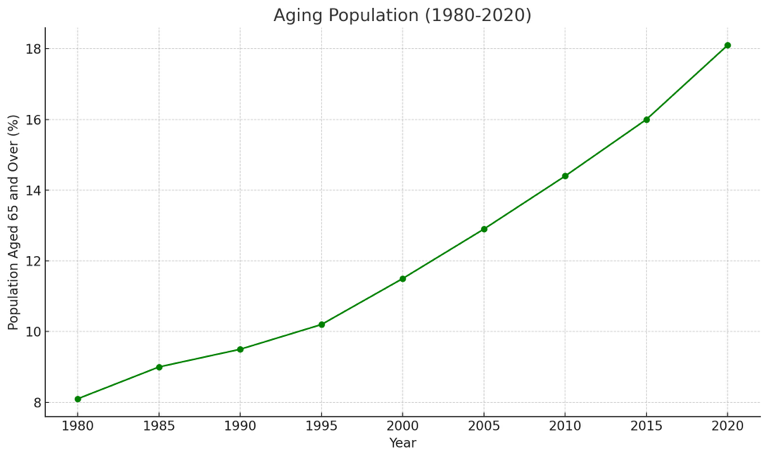

Well, when we have a look into the aging population, it looks like we’ve found our answer. From 1980-present day, the population aged 65 and over increased by 225%. However, we have the diagnostic data to show that this does not explain the whole rise. In fact, it only explains about half (450% increase in Dementia – Aging Population increase).

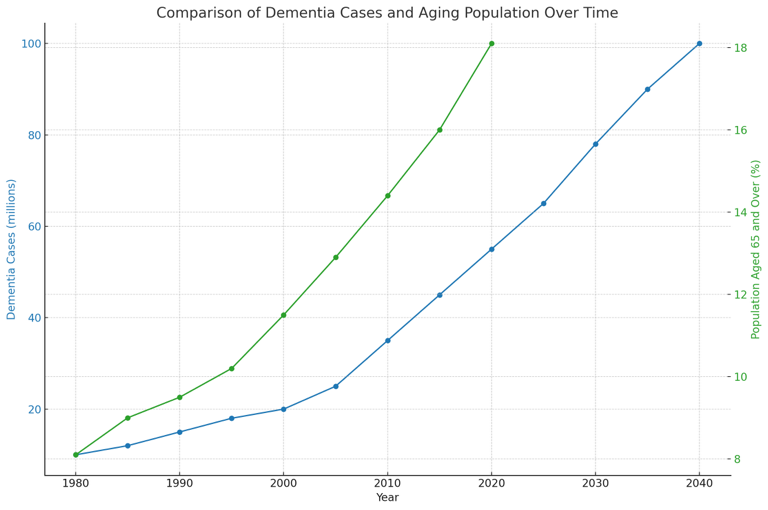

So, what happens when we compare the two graphs? Well, we see a parallel trend over time showing an upward trend on both. This correlated increase shows a strong relationship between the two, but still leaves a lot blank.

Therefore, we are left with diagnostic tools and lifestyle factors. In the year 2000, there was a discovery for amyloid-beta and tau proteins which are direct evidence of Alzheimer’s pathology. This allowed for more confident results, and enabled earlier intervention methods. While advancements in diagnostic tools play a crucial role in identifying Dementia, it is impossible to equate them within any factor explaining the epidemic due to no accurate data. This leads us into the growing interest into lifestyle factors, and how this influences the cognitive decline within individuals susceptible to debilitating conditions.

Among these, the ketogenic diet has emerged as a promising approach. This lifestyle significantly reduces carbohydrate intake and increase fat consumption, inducing a metabolic state called ketosis. In terms of individuals with recessive conditions, research has shown that entering this metabolic state increases blood ketone levels offering neuroprotective effects. Also, these ketones slow the rate of cellular degeneration due to its ROS regulation.

Several preclinical studies have confirmed a benefit of ketosis on cognition and systemic inflammation. Given the renewed emphasis on neuroinflammation as a pathogenic contributor to cognitive decline, and the decreased systemic inflammation observed with the ketogenic diet, it is plausible that this diet may delay, ameliorate, or prevent progression of cognitive decline.

To put it simply, multiple pilot studies and RCTs have shown that when individuals with Dementia are moved into a ketogenic state, their cognitive decline not only stopped slowing, but actually improved. Also, multiple gene-environment longitudinal studies showed that poeple with the genetic risk for dementia significantly benefitted from entering ketosis through either a reduction in formation, or increasing the age of fruition.

This is all because as Dementia progresses, the brain’s ability to utilise energy becomes hindered. As its only energy source is glucose, it means we run the risk of excaberating the metabolic dysfunction caused from such conditions. To be specific, high blood glucose, like the one found in unfit individuals on high-carb diets, lead to oxidative stress, one of the key factors involved with neurodegenerative diseases. Put simply, if you have Dementia, or are at risk of it, eating a higher carbohydrate diet could rapidly increase its progression.

One of the main features of Alzheimer’s disease is impairment of brain energy. Hypometabolism caused by decreased glucose uptake is observed in specific areas of the AD-affected brain. Therefore, glucose hypometabolism and energy deficit are hallmarks of AD.

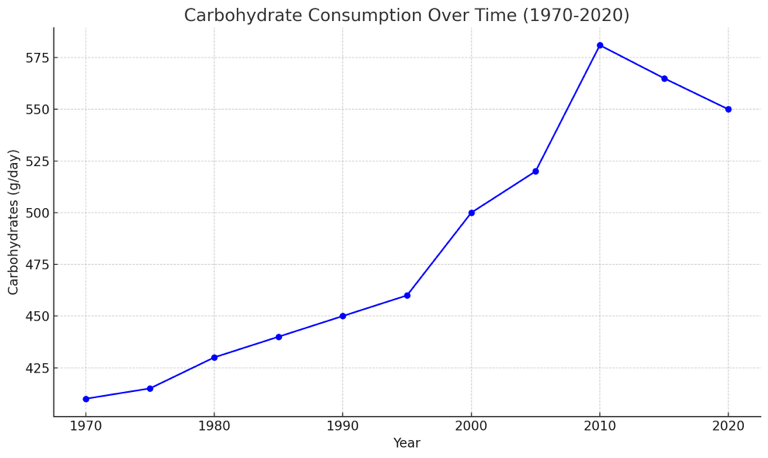

But, why is all of this so important? Well, when we take a glance at this graph below showing the daily carbohydrates eaten in grams per day, we might be able to understand one of the reasons Dementia diagnosis has skyrocketed.

This graph provides a crucial insight into dietary changes over the last few decades that may correlate with the increase in Dementia cases. Essentially, a general trend within the Western diet over the years has been an increased carbohydrate intake alongside a decreased dietary fat. This is due to biased research papers releasing information about dietary fats leading to weight gain, and also shifts in agricultural policy, such as leaning towards quick manufactured over whole foods. Such dietary trends have fuelled the upsurge of metabolic disorders, which are intrinsically linked with cognitive decline.

A hypothesis that gained wide support during the 1970s was that the diets commonly eaten in the USA and across the Western world had an excessively high content of fat and that this played a major role in various chronic diseases of lifestyle. This hypothesis was extended to obesity. In 1977, the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs translated this hypothesis into actual policy with the publication of Dietary Goals for the United States

Pointing to an alternative, the ketogenic lifestyle supports an abrupt reduction in carbohydrate intake, potentially reversing or relieving some disturbances caused by metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. These are not merely theoretical suppositions, but, in fact, practical solutions that have been trialed and implemented in RCTs.

In conclusion, considering the growing epidemic of Dementia, several factors that may severely contribute, such as dietary habits, must be taken into account. The ketogenic diet is one such area of interest for further research, and it, therefore, may be a practical way of slowing down the recessive nature of Dementia. In any case, further studies need to be carried out to fully understand its efficiency before recommending it as a feasible therapeutic approach.

Leave a comment