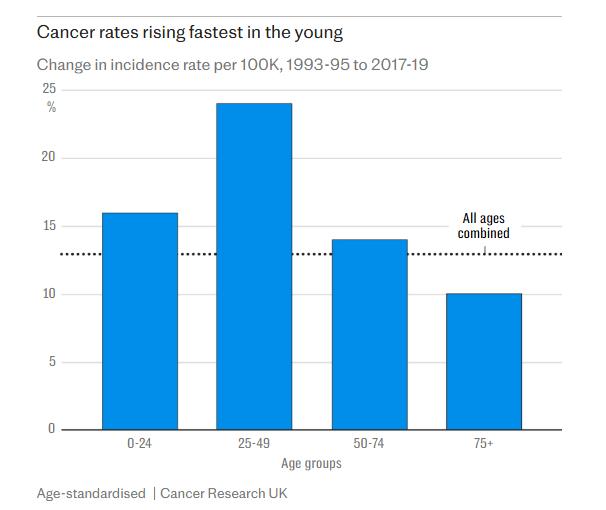

According to Cancer Research UK, British women under 50 are 70% more likely to develop cancer than men of a similar age. Similarly, US women are 82% more likely to develop cancer, compared to 51% two decades ago. As a result, we can now declare that there is a huge gender discrepancy in cancer rates, despite the global skyrocketing numbers being experienced in both sexes.

For this reason, it is vital that we investigate what changes have resulted in such worrying numbers, especially since women are developing oestrogen-related cancers more than any other (breast, cervical and endometrial).

Due to the speed at which this spread has occurred, being less than two decades, we must advocate investigating recent social phenomena. Therefore, this excludes genetic influence or any evolutionary factors, leaving us with environmental factors which include diet, exogenous influence, and general fitness. But even though we know obesity to be rising sharply, in theory, this is not the sole cause. Although women with a high fat mass have higher oestrogen levels, we are still seeing an increase in these hormonal cancer in fit and “healthy” under 50s.

One theory suggests that the increase in smoking and drinking, compared to historical levels, could be a reason. However, this also cannot be the sole reason, or at least, it is not a direct reason because lung cancer rates are still within their trend. However, we know that alcohol can stimulate the production of aromatase, the enzyme that converts testosterone to oestrogen. Therefore, for it to be a potential contributing factor, we start looking into oestrogen, especially given the sharp rises in men’s infertility and women’s precocious puberty.

From the water we drink and food we eat, to the clothes we wear and the air we breathe, exogenous oestrogens, those from outside the body, are everywhere, especially in the form of xenoestrogens (man-made). Unfortunately, longitudinal research on hormonal disparities didn’t exist 50 years ago, or even 30. So, declaring an official oestrogen epidemic is difficult. However, we can look at the symptoms of an oestrogen dominance and cross-compare these with the issues faced by the general female population within different stages of their biological clock.

Firstly, we have pre-pubescent girls. Within this stage of life, oestradiol levels are typically quite low, usually sitting around the 20 pg/mL (picograms per millilitre) margin. But, at around the age of 10, this starts increasing, with their bodies now producing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH), heralding the onset of puberty. But there’s a concerning trend: the average age at which puberty begins has been decreasing over recent decades, leading to an increased number of early and precocious puberty entries. This early onset is partly characterised by an excessive presence of oestrogen, which can cause the pituitary gland to create FSH and LH.

Historically, the most nutritionally advanced girls entered puberty much later, with records showing the euro-wealthy having their first menstruation at 16. Therefore, this could hint at the modern environment as a culprit to the decreasing puberty age, potentially leading to what we could call an ‘oestrogen dominance’, where this hormone rises disproportionately to progesterone, its counterpart. Most cases of precocious puberty are characterised by premature pituitary gland activation and involve an elevated oestrogen level. However, this can also work the other way around. For example, if we were to inject an 8-year-old girl with oestrogen, her hypothalamus would activate and start producing FSH and LH, forcing her to enter puberty, which may explain the sudden drop in puberty age.

As women enter their reproductive years, typically attributed to 18–40-year-olds, the complexity surrounding their hormonal relationships cannot be underestimated. While oestrogen dominance is the central theme, an incorrect ratio between this and progesterone is one of the culprits to the rising rates of PCOS, infertility and cancers.

One of the most significant health conditions faced by Western women of reproductive age is PCOS, a condition innately comprised of hormonal imbalance, especially in the form of oestrogen to progesterone ratios alongside thyroid stimulation. While the primary symptoms of PCOS – irregular periods, infertility and metabolic disturbances – are well documented, women with PCOS are 2.7 times more likely to develop endometrial cancer compared to those without the condition. This elevated risk, primarily attributed to the prolonged exposure to unopposed oestrogen, can progress to cancer over time. One study even references a 15 times higher risk, showing the urgency for intervention at a young age. However, PCOS is not the only condition women of reproductive age face. We also have endometriosis, uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, PMS and PMDD, and many mood disorders, all of which are characterised by an elevated oestrogen level and increase the risk of our three rising cancers.

But unfortunately, the issues don’t stop here. After the reproductive years, the next big step is menopause. Currently, the US menopause market is valued at $5.3 billion, with it expected to reach $7.3 billion by 2030. Primarily driven by two categories: dietary supplements and over-the-counter pharmaceuticals, with the former making up 93.9% of revenue share, this huge revenue reflects the growing demand for menopause symptom mitigation alongside the number of women entering it each year. While this stage of life is a normal part of every woman’s life, it seems that the average menopause experience is worsening through the growing revenue share from relevant markets.

The increasing prevalence and severity of symptoms that we are seeing may be linked to environmental factors due to the speed of change, similarly to cancer rates. For example, research shows that total environmental quality is significantly associated with breast cancer, especially in urban areas. Poor environmental quality, especially in terms of air, has this positive association. These factors may be exacerbating the hormonal imbalances women experience during menopause. For instance, exposure to environmental pollutants and toxic chemicals such as particulate matter and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are being investigated as potential risk factors for breast cancer, particularly in the menopause transition.

Interestingly, the impact of our environment on menopausal symptoms and cancer varies amongst geographical locations. For example, women living at higher altitudes tend to report less severe symptoms compared to their counterparts and have lower cancer mortality rates. Some studies suggest that this could be due to the adrenal function as a result of reduced oxygen levels and increased cerebral perfusion (blood flow to the brain), but that’s for a different article.

Given these obviously alarming trends, it is important women are given the knowledge to explore actionable strategies to mitigate the risks. Taking the simplified logic of oestrogenic cancer, we must lower oestrogen levels to reduce the risk. However, as women are still getting these cancers post-menopause, it means we must reduce the exposure before it becomes “prolonged”.

Depending on the symptoms and condition, we turn to progesterone, the antagonist of oestrogen. Progesterone therapy, oral or dermal, has had significant improvements on women with PCOS and menopause, with symptoms being reduced in almost all cases. Due to progesterone’s anti-oestrogenic capabilities, supplementation allows the hormonally imbalanced to experience more regular cycles, sleep patterns and metabolic effects.

While this is not a solution, especially due to the fact that no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach exists, it is a bandage that has been seen to work in a majority of cases. For instance, many RCTs have shown that micronised progesterone is effective at treating vasomotor symptoms in menopausal women, depression and anxiety for those with a mood disorder, and has even provided regular cycles to those diagnosed with PCOS. However, individual results may vary, and it is important to consult a healthcare provider to determine the suitability and risks of progesterone therapy. But this is not the only step one can take. Reducing the use of xenoestrogens is also beneficial.

Unfortunately, we in the West have xenoestrogens absolutely everywhere. They are in the clothes we wear, the personal care products we use (moisturiser and shampoo, for example), household cleaning products, and even the water we get from our sinks. Now, I am not advocating for a reverse osmosis filter in every single household. Instead, I am recommending we learn about the xenoestrogens put into our environment and try to mitigate them in places we want.

Overall, the rising rates of oestrogen-related cancers and hormonal imbalances in women, particularly across key life stages from pre-puberty to menopause, paint a concerning picture. While environmental xenoestrogens pose a significant challenge, awareness and proactive choices offer a path forward. By reducing exposure through lifestyle adjustments like choosing natural products and filtering water, and by partnering with healthcare professionals for personalized guidance and potential progesterone therapy, women can actively work towards hormonal balance. It’s time to empower ourselves with knowledge, demand safer products, and prioritize our well-being in an increasingly oestrogenic world.

Leave a comment