Alcohol damages the liver. This statement has been continuously propelled to us for generations, encouraging younger generations to reduce consumption, with some even abstaining completely.

Since the 1950s, we have seen a significant increase in per capita diagnoses of Alcohol Liver Disease (ALD), with lower-income groups bearing most of the damage despite higher binge drinking rates in wealthier households. This unexpected inverse relationship raises intriguing questions regarding alcohol consumption and its impact on liver health. Could it be that the statement “alcohol damages the liver” fails to capture the complexity of such a costly issue? Perhaps it is an oversimplification, and there are hidden variables that influence perceived consequences. Therefore, this leads us to search for possible factors that have been previously ignored.

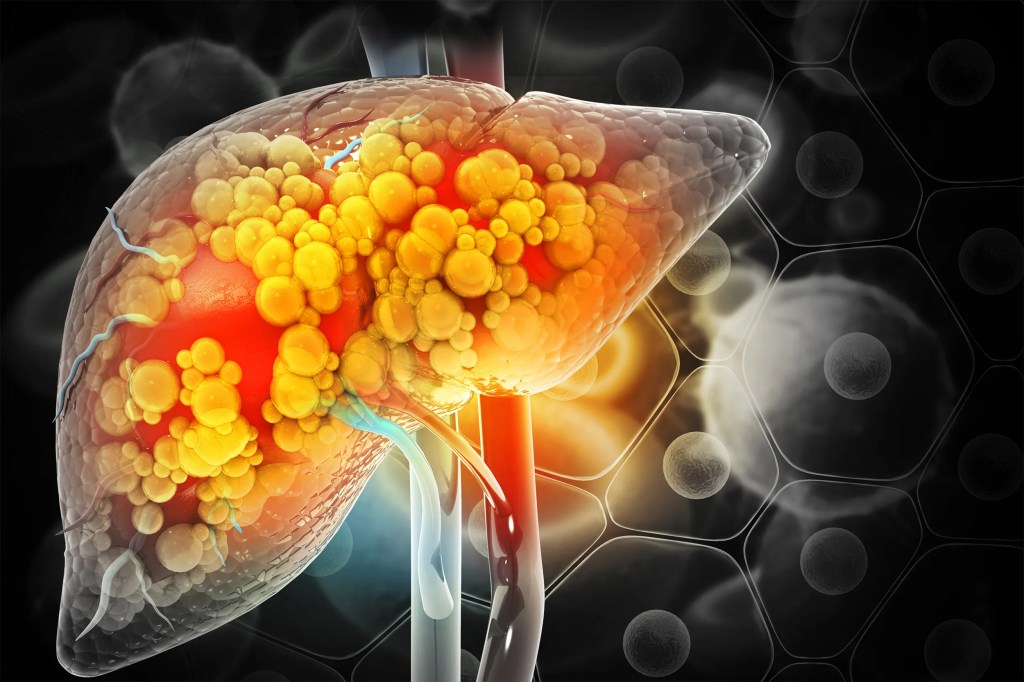

The liver, a vital organ responsible for filtering toxins, regulating our blood sugar, and aiding digestion, acts as a mystical healer with its ability to regenerate damaged cells at will. However, prolonged damage from substances like alcohol diminishes its regenerative ability, leaving it unable to repair.

While the message that “alcohol damages the liver” is undeniably true, it is part of a dangerous oversimplification of a widely environmental issue.

Firstly, we have genetics. It is widely known across scientific literature that our specific genetic coding has an impact on how we metabolise alcohol, specifically the ADH and ALDH variants. However, since the ALD surge started in 1950, and our genes have not drastically changed within 75 years, we can suggest that they cannot be the main culprit in ALD’s proliferation.

Therefore, we need to examine factors that have significantly changed since this surge started, leading us into body composition. In our modern era, it is a correct assumption that our body fat percentages have become a culprit of many issues. From cancer and diabetes to suicidality and metabolic dysfunction, our body fat has skyrocketed to exorbitant percentages. As a result, it would not be incorrect to assume a similar conclusion with ALD, especially due to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis being common comorbidities.

Typically, the liver is a relatively fat-free organ. However, if we were to add fat cells to this vital piece of our human puzzle, it would interfere with its ability to function effectively. Usually, levels beyond 5% would justify as high enough to trigger fatty liver symptoms such as limb swelling, yellowing of the skin, weakness, and persistent itchiness.

As expected, this accumulation of fat is something seen often in cases of alcohol liver disease. Even though it is not the only problem caused by ALD, fatty liver is one of the earliest and most common factors involved in its complications, making it a vital talking point. The pathogenesis of ALD simply increases the synthesis of fatty acid oxidation within the liver due to a skewed NADH/NAD+ ratio. In other words, the liver’s ability to break down and metabolise fats becomes severely impaired, causing them to accumulate within the organ.

As a result of this bodily process, we would assume that cutting out the fat would help protect ourselves from fatty liver issues, especially when high amounts of alcohol are present. However, unfortunately, nothing is ever that simple. When we look at how the liver is affected by dietary stimuli alongside alcohol, the type of fat seems to have a huge impact. For example, high levels of saturated fats reduce the risk of incident alcohol liver disease and mitigate alcohol-induced damage by reducing total oxidative stress. Not only this, but saturated fat consumption helps maintain proper gut barrier integrity, reducing endotoxemia (toxic leaking into the blood) and subsequent liver inflammation.

On the other hand, high omega diets, consisting of our unsaturated fatty types, promote oxidative stress and fat accumulation within the liver. Unlike saturated fats, which are completely stable due to their singular cohesive bond with hydrogen molecules, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) have a double bond, meaning they are not fully saturated. In other words, these double bonds are more exposed to oxidisation.

Imagine two bridges spanning a turbulent river, each designed to support the same weight but constructed differently.

The first bridge, representing saturated fat, is supported by one singular metal rod. This beam is robust and highly resistant to the river’s constant flow and occasional debris. Its solid foundation makes it less susceptible to corrosion and structural fatigue.

The second bridge, symbolising an unsaturated fat molecule, relies on two thinner steel cables for support. While made of the same material and combining to equal the same mass as the first bridge, its individual vulnerability is greater. The rushing water and occasional debris cause wear against the cables, gradually weakening their structure.

In this analogy, the flow of the river represents oxidative stress and free radicals within our body. The thick beam of saturated fat remains largely unaffected, similarly to how they resist oxidation. But the thinner cables of unsaturated fat are more reactive to their environment, becoming prone to peroxidation.

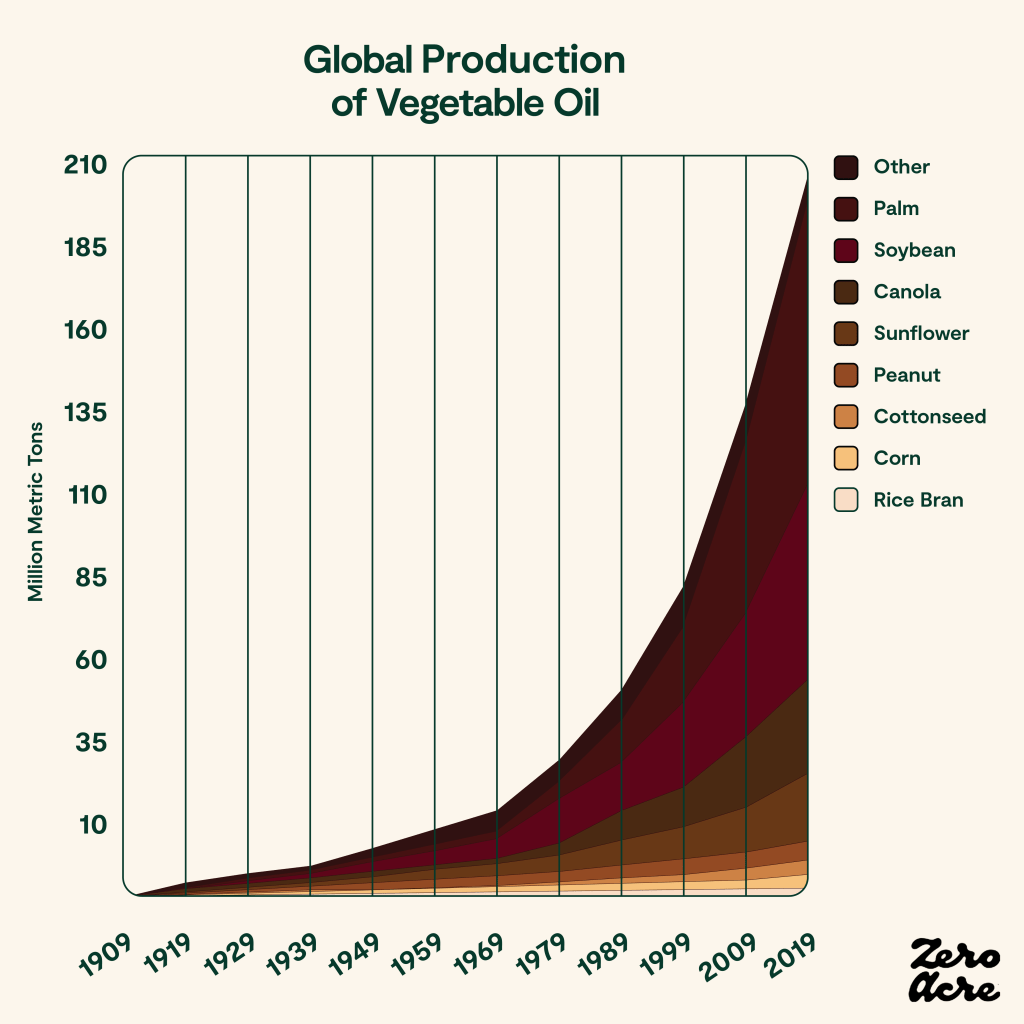

But what contains these unsaturated fats that could be causing such a big issue in the ALD sphere? As we have explored, ALD started rising in the 1950s, coincidentally around the same time as vegetable oils were becoming mainstream. These homogenous oils are predominantly made from unsaturated fats and are found in almost all our ready meals, treats, and fast food. Not only do we accidentally consume them almost daily, but government science suggests they are “heart healthy” and a vital part of a person’s diet.

The proof is literally in the pudding.

Linoleic acid, the primary omega-6 PUFA in vegetable oils, is particularly problematic. Its double bond structure, thinking back to the bridge, makes it susceptible to oxidation. When linoleic acid is oxidised, it produces harmful byproducts like OXLAMs and ROS. Also, a diet high in these oils creates a fatty acid imbalance, promoting liver inflammation and steatosis.

As a result, we create a vicious cycle where alcohol impairs the liver’s ability to metabolise unsaturated fat, while linoleic acid and other high omega fatty acids run rampant, increasing the likelihood of their oxidation.

So, where does this leave us? The saying “alcohol damages the liver” remains true, but it’s a half-truth at best. It’s not just the alcohol; it is the environment in which it’s consumed. Body composition sets the stage, and dietary choice amplifies the risk, either allowing the body to shield or sabotage. The rise of ALD since the 1950s cannot be simply attributed to increased consumption; rather, it should serve as evidence for an urgent need to rethink our modern diet and return to the nutritional foundations of the past.

Leave a comment